Newsletter Sign Up

Sign up today to our quarterly newsletter

View more

If you only see one meteor shower this year, make it the Geminids. Widely regarded as the finest meteor shower visible from the southern hemisphere, the Geminids return each December with reliable rates, bright meteors, and long, graceful streaks across the sky.

In 2025, conditions are lining up beautifully for observers across Western Australia, with a favourable Moon phase and peak activity occurring at an ideal time for evening and late-night viewing.

The Geminids will peak on the night of Sunday 14 December into the early hours of Monday 15 December 2025, with the strongest activity expected between 10.00 pm and 2.00 am AWST.

The shower is active for around two weeks, from 4 to 17 December, so even nights either side of the peak can still deliver an excellent display, particularly from darker locations.

This year, the Moon will be a Waning Crescent, rising late and producing minimal interference. That means dark skies for much of the night and far better meteor visibility than in years dominated by a bright Moon.

Under typical suburban conditions in Perth’s outer suburbs and the Perth Hills, you can expect to see around 10 to 15 meteors per hour during the peak.

If you can get to a genuinely dark site around Western Australia, particularly away from city glow, rates can jump significantly. In these dark locations, observers may see 30 to 50 meteors per hour, and occasionally even more during short bursts of activity.

Closer to the equator, where the Gemini constellation rises higher in the sky, observers can see 40 to 70 meteors per hour, which is why the Geminids are considered a global favourite.

The meteors appear to radiate from the constellation Gemini, which is where the shower gets its name. This point in the sky is known as the radiant.

Importantly, you should not stare directly at Gemini. Instead, look 30 to 45 degrees away from the constellation, either to the left or right. Meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but this viewing angle gives you longer streaks and a better chance of spotting bright fireballs.

If you trace the paths of the meteors backwards, they all appear to lead back to Gemini, even though they flash into view far from it.

The Gemini constellation rises in the east at around 10.00 pm, and as it climbs higher through the night, the meteor rates increase. This is why the best viewing occurs after midnight, though excellent activity can still be seen earlier in the evening during the peak.

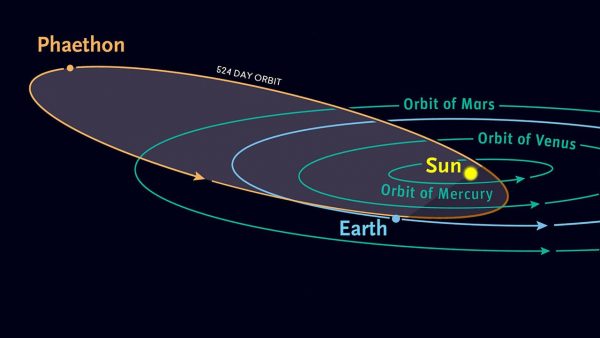

Unlike most meteor showers, which originate from comets, the Geminids come from an object that blurs the line between asteroid and comet.

The shower is caused by Earth passing through debris left behind by asteroid 3200 Phaethon, which was discovered in 1983. Although classified as an asteroid, Phaethon behaves like a “rock comet”. It has shown evidence of surface activity and produces streams of dust when it is heated intensely as it swings close to the Sun.

As Earth ploughs through this ancient debris trail, tiny dust particles slam into our atmosphere at tremendous speeds. Friction with the air causes them to heat up and vaporise, producing the bright streaks of light we see as meteors.

The Geminids were first observed in 1862, making them one of the younger major meteor showers known to science, yet today they are among the most prolific and reliable of all annual displays.

Unfortunately, Perth Observatory’s Geminids event for 2025 is now sold out, but the good news is that meteor showers are best enjoyed with nothing more than dark skies, warm clothes and patience.

If you want to stay relatively close to the city, locations such as:

all offer significantly darker skies than central Perth and should provide an enjoyable viewing experience.

For the truly unforgettable Geminids experience, travelling further afield into Western Australia’s Central Wheatbelt is highly recommended. Even a simple roadside rest area can deliver spectacular skies, with the Milky Way blazing overhead and meteors appearing every few minutes at the peak.

Beyond the sheer visual impact, heading to the country also supports regional towns and lets you experience some of Western Australia’s most beautiful night-time landscapes without spending large amounts of money.

No telescope or binoculars are required, your naked eyes are the best tool for meteor watching.

With favourable Moon conditions, excellent timing, and consistently high meteor rates, the 2025 Geminids Meteor Shower shapes up as the best celestial event of the year for Western Australia.

Whether you are watching from the Perth Hills, a quiet beach, or under the pristine skies of the Wheatbelt, this is one event well worth staying up late for.

Clear skies and happy meteor watching from all of us at Perth Observatory.

Sign up today to our quarterly newsletter

View more

Let others know of your experience

View more

Become an awesome volunteer

View more